BY CAROL BAASS SOWA

TODAY’S CATHOLIC

SAN ANTONIO • An unprecedented gathering of Spanish colonial works of art, predominantly from the great museums of Mexico, is offering visitors to the San Antonio Museum of Art a look at San Antonio from 1718 to 1818 through the lens of art.

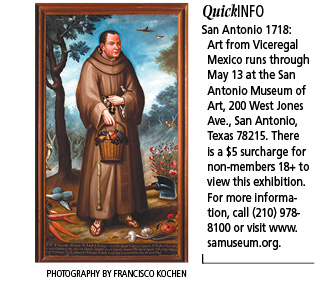

San Antonio 1718: Art from Viceregal Mexico, which runs through May 13, is the museum’s salute to San Antonio’s tricentennial. Carefully assembled by Curator of Latin American Art Marion Oettinger in what he calls “a five-year treasure hunt in the great museums and private collections of Mexico,” the exhibition also selectively borrowed from across the United States and includes some of the few remaining local pieces from San Antonio’s first century as well.

San Antonio 1718: Art from Viceregal Mexico, which runs through May 13, is the museum’s salute to San Antonio’s tricentennial. Carefully assembled by Curator of Latin American Art Marion Oettinger in what he calls “a five-year treasure hunt in the great museums and private collections of Mexico,” the exhibition also selectively borrowed from across the United States and includes some of the few remaining local pieces from San Antonio’s first century as well.

The undertaking proved daunting, related Oettinger, who noted there was no art from San Antonio for the first century. “With the exception, of course,” he added, “of our extraordinary cultural jewels, the missions themselves, and then a handful of pieces like the (San Fernando Cathedral) baptismal font and some of the beautiful murals in the missions and a couple of other pieces that we know were part of the 18th century inventories.”

Local pieces include the gilded and polychrome wood statue of St. Joseph (ca. 1770) from Mission San José’s present retablo, courtesy of the Old Spanish Missions Center, and an 18th century portrait of Mission San José’s founder, Fray Antonio Margil de Jesús, on loan from Our Lady of the Lake University. Beyond these “familiar faces,” the exhibition features a smorgasbord of spectacular paintings, most never seen outside Mexico before, along with secular and religious objects from that time – intricately carved chests, silver Santo Niño de Atocha alms dish and pictorially-embroidered rebozo among them.

Local pieces include the gilded and polychrome wood statue of St. Joseph (ca. 1770) from Mission San José’s present retablo, courtesy of the Old Spanish Missions Center, and an 18th century portrait of Mission San José’s founder, Fray Antonio Margil de Jesús, on loan from Our Lady of the Lake University. Beyond these “familiar faces,” the exhibition features a smorgasbord of spectacular paintings, most never seen outside Mexico before, along with secular and religious objects from that time – intricately carved chests, silver Santo Niño de Atocha alms dish and pictorially-embroidered rebozo among them.

Oettinger and his staff began to notice patterns as they combed museums for art treasures relating to San Antonio’s early years. Gradually, they divided their finds into the three categories of the exhibition: People and Places (persons and towns fundamentally involved in the exploration, settlement and evangelization of San Antonio); The Cycle of Life (the various types of people and typical scenes in northern New Spain); and The Church (saints, religious orders and sacred rituals and objects). Oettinger referred to this last grouping as “the most powerful and the most poignant.” Spatially, they cover from Mexico City to a little north of San Antonio.

Visitors will have an inkling of what lies ahead as they enter the museum lobby and are greeted by a massive oil painting depicting the “family tree” of the Franciscan order, founders of San Antonio’s missions. Typical of paintings in monasteries all over Mexico and Spain at that time, this was a didactic tool showing saints, martyrs, popes, cardinals, and leaders of the order, along with sympathetic kings and queens.

Visitors will have an inkling of what lies ahead as they enter the museum lobby and are greeted by a massive oil painting depicting the “family tree” of the Franciscan order, founders of San Antonio’s missions. Typical of paintings in monasteries all over Mexico and Spain at that time, this was a didactic tool showing saints, martyrs, popes, cardinals, and leaders of the order, along with sympathetic kings and queens.

Inside the gallery, a set of 15 richly detailed caste paintings fills an entire wall. A popular 18th-century genre, they show the various types of racial mixing in New Spain and Latin America, each having its own name and ranking in a hierarchy of castes, pure Spanish, of course, being at the top. All the paintings’ subjects were treated with respect by the artist, however, and the castes were actually very fluid.

“If somebody arrives and they clearly demonstrate that they’re good citizens, they work for the church, they give to the poor, they volunteer their time for the wellbeing of the community,” related Oettinger, “you will see their reputation and their designation changing as well.” And if by luck or hard work, someone acquired enough wealth, they could purchase a title from the king and become nobility.

The idea, he noted, was to build a mixed population as a labor source, whereas in the United States, native populations were removed or eliminated. Workers were especially needed in New Spain’s mines, which moved north, much of this fueled, said Oettinger, by “the eternal dream of El Dorado, this mythical city of gold.”

There are portraits of movers and shakers who played a role in the development of northern New Spain — Spanish-born, mestizo and even a Frenchman. One was Bernardo de Gálvez, for whom Galveston was named, whose naval operations helped the United States win the American Revolution.

A 1722 illustration, using a presidio template, shows San Antonio’s presidio between the Rio San Antonio and Rio San Pedro (San Pedro Creek); period death portraits chronicle passings from an infant’s to a nun crowned in death with the floral headpiece from the day she took her vows; family portraits display status and occupation.

A 1722 illustration, using a presidio template, shows San Antonio’s presidio between the Rio San Antonio and Rio San Pedro (San Pedro Creek); period death portraits chronicle passings from an infant’s to a nun crowned in death with the floral headpiece from the day she took her vows; family portraits display status and occupation.

The exhibition culminates in the section on church, with attention paid to the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception and her American apparition as Our Lady of Guadalupe. A painting by Cristóbal de Villalpando, thought to almost certainly have been commissioned by Father Margil, depicts St. John the Evangelist and Sor María de Jesús de Ágreda, the Spanish mystic whose writings on the Immaculate Conception inspired the evangelization of the Americas. They look upward to the Immaculate Conception, who is flanked by archangels Michael and Gabriel, Franciscan favorites.

At an adjacent painting of Our Lady of the Rosary, who floats above a mining town in northern Mexico, Oettinger paused to point to the rolling hills in the distance and surmise, “Right on the other side of that hill is San Antonio.” On another wall, a stunning full-length portrait of a white garbed novice is, he related, often said to be the best portrait painted in New Spain.

The final rooms are an homage to St. Francis and the Franciscan order he founded. An immense and especially significant painting here is José de Páez’s Martyrdom of Franciscans at Mission San Sabá, the oldest known painting depicting Texas.  It graphically depicts, in multiple scenes scattered across a Hill Country setting, the destruction of Mission San Sabá by Comanches and other tribes aligned with the French and the grisly martyrdom of the mission’s two friars. These are but a few of the exhibition’s fascinating pieces and stories.

It graphically depicts, in multiple scenes scattered across a Hill Country setting, the destruction of Mission San Sabá by Comanches and other tribes aligned with the French and the grisly martyrdom of the mission’s two friars. These are but a few of the exhibition’s fascinating pieces and stories.

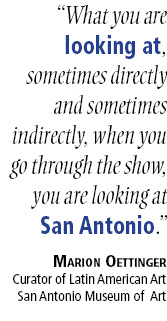

“What you are looking at, sometimes directly and sometimes indirectly, when you go through the show, you are looking at San Antonio,” said Oettinger. “That’s what we are interested in telling, the story. There was a history before the Alamo.”