By J. Michael Parker

For Today’s Catholic

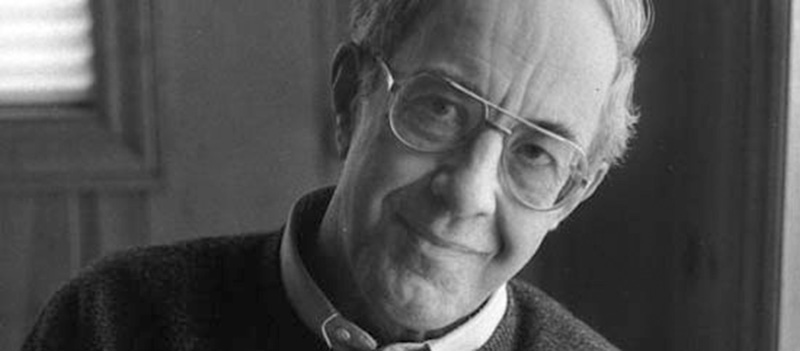

Henri Nouwen’s copious writings on spirituality gave his readers two great gifts — vulnerability and compassion — according to a Toronto nun who knew Nouwen at the L’Arch Daybreak community during the last decade of his life.

Most people don’t like vulnerability. “We don’t want to be there, and we don’t want others to see it — but we all have it and it’s not going to go away. It’s not because we deserve it; we didn’t do anything wrong so that it happened to us,” said Sister Sue Mosteller, CSJ, the executrix of Nouwen’s archives. She addressed some 400 people at OST’s 2017 Summer Institute June 19-21 at the school’s Whitley Theological Center.

Nouwen taught her that suffering and vulnerability are “a mystery not to be solved but to be lived.” Compassion and vulnerability were uniquely present in Nouwen in a certain way, as they are in each of us and as they were in the life of Jesus, she explained. Mosteller pointed out that Jesus walked among people and was in relationship with them — “maybe for only a few minutes, but something changed because of that relationship,” she observed.

In living and experiencing compassion and vulnerability, she continued, Nouwen often spoke of “the fellowship of the weak.” Most of us run from that, she observed, but “this is a checkpoint for each of us to ask, ‘What am I invited to live at this moment? ‘Who can hold me and live this mystery — not to solve it but to live it well, to welcome the fact that I’m not God and I am allowed to suffer?’ Henri’s whole life was about announcing something of what he himself had learned and experienced.”

She commented that Nouwen never sought pity for his own pain and suffering, but used it to enter the struggles of others and encourage them to find good ways to live their struggles rather than blame someone else for either imposing it or ignoring it.

When he was invited to L’Arch Daybreak to be the pastor of the community for people with disabilities, leaders were grappling how to plan meaningful worship services that were comfortable for people of diverse religious backgrounds. Nouwen listened to a discussion of the problem and completely changed the atmosphere simply by suggesting they change the word “problem” to “gift.” Soon the services began to recognize the beauty in each tradition. She recalled a Muslim funeral attended by 200 Muslims and 40 non-Muslims. The Muslim custom of closing the casket meant that non-Muslims could not gather around the body to tell stories about their deceased friend; however, the imam announced that the casket would be opened for that purpose, and the non-Muslims told their stories and celebrated their friend’s life. Afterward, the Muslims accepted an invitation to a memorial service in the Christian chapel. The experience brought the whole community closer together.

“Henri’s gift in helping us not to be afraid of suffering was very important,” Mosteller said. Then he had a serious breakdown. “I’ve never witnessed someone who suffered as much as Henri did. He was a broken man, unable to function. He knew enough to say, ‘I can’t stay here; you can’t support me. I have to go away,’ and he went to Winnipeg for seven months.”

He lived very quietly it in immense suffering, the nun said. A friendship had ended suddenly, and the break precipitated everything in Nouwen’s life: his broken self-image, his belief that he was not a wise or a good person, and his shame all crashed in in him, Mosteller explained. During those months, he studied the poster of Rembrandt’s famous painting The Return of the Prodigal Son. When she visited him, he spoke of his entrance into the Prodigal Son parable. “Henri didn’t read the gospel; he was in the gospel,” she said.

In time, she realized that that’s the way Nouwen read Scripture, particularly the Prodigal Son story. “He didn’t read it and say, ‘That’s a nice story about two boys and their father’; he became the younger son and he became the elder son; and then he realized his journey was to become the father.”

Returning from Winnipeg, fragile and sad, to live out what he had learned there, “he nevertheless began to live his paternity in a way his friends at Daybreak had never seen. Every time somebody was leaving, he’d give a blessing.’”

“Henri was exercising his paternity, encouraging us and saying, ‘Stand up; you don’t have to say ‘I can’t do it.’ You can be kind, you can look at people and give a good word. Try not to hold back your emotions. We so much need the blessings.”

Nouwen often told the community, “You and I are gifted with compassion and vulnerability. We were all born in the image and likeness of God, which means we’re like God. We have love; we have energy, goodness, kindness and hope. Planted in every one of us are the maternal and paternal gifts. We’re made to be mothers and fathers, physically, psychologically and emotionally — not just to have our children and raise them up; that’s the training ground for our whole lives,” Mosteller quoted him as saying. “Each of us is invited to realize that those gifts, both maternal and paternal — protection, care, goodness, love, trust, affirmation, hope — those gifts are in us, but nobody is calling them forth,” adding, “That’s what Henri was doing.”

Mosteller said that using those gifts is “meeting the adolescents that live inside of us and inviting them to leave, because now we’re mothers and fathers. Who are the adolescents who say, ‘I don’t care, I can just waste my time and play video games when I could be visiting somebody who’s dying, stopping to look at someone in need, or caring about someone in my home who’s been close to me but we’ve grown apart?’ Look again, and recognize the diamond, the beauty, the energy, the depth, that’s been given to each of us by the God who has laid down his life for us and wants us to lay down our lives for each other.”

Mosteller ended her lecture by reading a passage near the end of Nouwen’s book The Return of the Prodigal Son. “’When the younger son returns to his father, it’s not to remain a child but to claim his sonship as the returned child of God who’s been invited to resume my place in my father’s home, and to become the father himself.’” But Nouwen said that while he had realized early that returning to his father’s home was his own call, it required much spiritual work to make the elder son and the younger son inside him turn around and return home. On many levels, he said, he was still returning. But, Mosteller read, “‘the closer I come to home, the clearer it becomes to me — the realization that there’s a call beyond the call to return—it’s the call to become the father who welcomes home and calls for a celebration.’”

In his last paragraph, Sister Mosteller said, Nouwen expressed awe at the place where Rembrandt brought him — “‘from the kneeling, disheveled young son to the standing, bent-over father, from the place of being blessed to the place of blessing. A I look at my own aging hands,’” she read, “‘I know they have been given to me to stretch out to all who suffer, to rest on the shoulders of all who come and to offer the blessing that emerges from the immensity of God’s love.’”