BY CAROL BAASS SOWA

TODAY’S CATHOLIC

SAN ANTONIO • Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo, with its ornately carved facade, was the result of friendly rivalry between its Franciscans from Zacatecas with the those from Queretaro at Mission Concepción and it was San José that became known as the “Queen of the Missions.”

At secularization in 1794, San José’s holdings were distributed among its approximately 96 inhabitants, but by 1824 their communal life had declined, many of the old perimeter living quarters had disappeared and properties had changed ownership. Revolutionary upheavals brought further deterioration.

In the 1850s, Bishop John Odin, first bishop of the Diocese of Galveston (which included San Antonio), became the first of many bishops who sought to save the crumbling ruins. He purchased large sections of the compound and attempted to re-staff the missions with Conventual Franciscans, working in 1854 with Father Leopold Moczygemba of Panna Maria, who went so far as to buy part of the convento himself, but plans fell through and the Conventuals left Texas a few years later.

Bishop Odin then turned to the Benedictines, who began extensive reconstruction following their 1859 arrival. They added the brick lancet arches to the convento, which they planned to raise to three stories, but with the Civil War, funds ran short and they departed in 1868, leaving the convento two stories high and roofless. By then, large sections of the north wall of the church nave had fallen.

Bishop Claude Dubuis, second bishop of the Diocese of Galveston, turned to the Holy Cross fathers of Notre Dame, Ind., transferring San José’s title to Notre Dame University in 1873. However, during midnight Mass in 1874, the dome and vaulted roof of the church collapsed, marking what appeared to be the end of the old mission church. Soon the shell of the former “Queen of the Missions” stood roofless, with walls tumbling down, front doors stolen and the lovely façade statues mutilated. Pieces were sold as souvenirs.

Bishop Claude Dubuis, second bishop of the Diocese of Galveston, turned to the Holy Cross fathers of Notre Dame, Ind., transferring San José’s title to Notre Dame University in 1873. However, during midnight Mass in 1874, the dome and vaulted roof of the church collapsed, marking what appeared to be the end of the old mission church. Soon the shell of the former “Queen of the Missions” stood roofless, with walls tumbling down, front doors stolen and the lovely façade statues mutilated. Pieces were sold as souvenirs.

San José and the other missions seemed destined to become as forgotten as their names. Save for Mission San Antonio de Valero, revered as the Alamo, by the turn of the century it was becoming common to refer to the missions by number instead of name, based on distance from town. San José, second farthest, was the “Second Mission.”

The start of the 19th century brought new hope. Devout Catholic Adina de Zavala led the Daughters of the Republic of Texas in raising funds and materials for mission repairs, among them bracing the still standing front wall of San José’s church in 1902. Later, Ethel Drought, also a devout Catholic, found the heavy wood steps of the spiral choir staircase collapsed and paid for their restoration, as well as the sacristy’s.

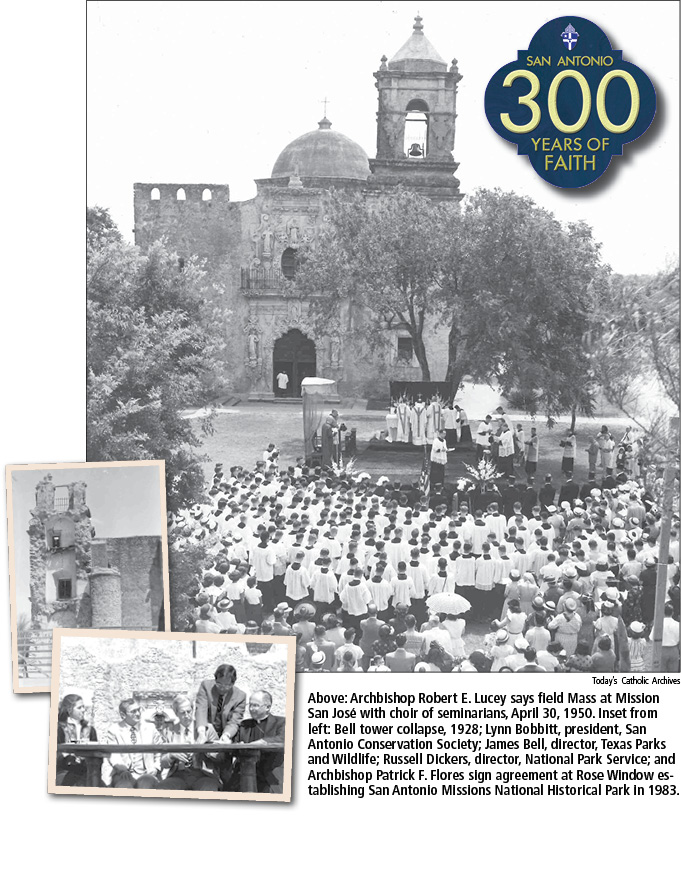

When part of San José’s bell tower collapsed in 1928, Archbishop Arthur Drossaerts enlisted architects Atlee Ayres and Fred Gaenslen to oversee rebuilding and set out to restore the entire mission in the 1930s, partnering with the San Antonio Conservation Society (SACS) and the Works Progress Administration, under architect Harvey P. Smith. SACS purchased San José’s granary, restored it and then leased the granary and several rooms to Ethel Wilson Harris to revive traditional craft skills on the premises. The Franciscans returned in 1931.

In 1941, Mission San José State Park was created and San José designated a National Historic Site, thanks to an advisory board that included the archdiocese, the Secretary of the Interior, the National Park Service (NPS), the Texas State Parks Board, Bexar County Commissioners Court and SACS. Their agreement transferred management to the State Parks, with Ethel Harris manager, while the archdiocese retained control of the church.

Archbishop Robert E. Lucey undertook restoration of San José’s ornate limestone façade in 1948, hiring Italian sculptor Ernest Lenarduzzi of Houston, who added some touches of his own as well. The work was done under the supervision of Father (later, Msgr.) Roy Rihn as the archbishop’s “special representative.” Lenarduzzi was guided by early prints of the mission obtained from Bishop Mariano Garriga of Corpus Christi, who had been superintendent for mission restoration in the 1920s. Traces of San José’s original colorful exterior designs, which were chemically analyzed and copied in the 1930s by Ernst Schuchard, were replicated on part of the south wall in 1948.

A new restoration surge at the missions began in the 1960s, with Ford, Powell & Carson, the archdiocese’s architects from then to the present. In preparation for HemisFair ’68 visitors, Father Balthasar “Balty” Janacek was appointed director of the four diocesan missions in 1967, a position he held ‘til his death in 2007. They were eventful years.

From 1978 to 1983, work progressed on a unique, agreement that turned the four missions into San An- tonio Missions National Historical Park, with the NPS managing grounds and non-church structures, while the archdiocese maintained churches and parish buildings for these still active parishes. Auxiliary Bishop Charles Grahmann was instrumental in clearing a key roadblock to this.

In 1981, the Old Spanish Missions, Inc. was officially incorporated as the archdiocese’s mission fundraising arm under now Msgr. Janacek, with Father David Garcia succeeding him in 2007 and leading the recently completed restoration, which included intensive repair and preservation work on San José’s magnificent facade carvings, making San José once again “Queen of the Missions.”

Next: Mission San Juan Capistrano