Polish immigrants follow priest’s call to Texas

Written by Carol Baass Sowa

Today’s Catholic

We are all immigrants or descendants of immigrants. While today’s immigrants are of different origins than in the past, they are drawn to America and Texas for the same reasons our forefathers came and similarly faced hardships and prejudices.

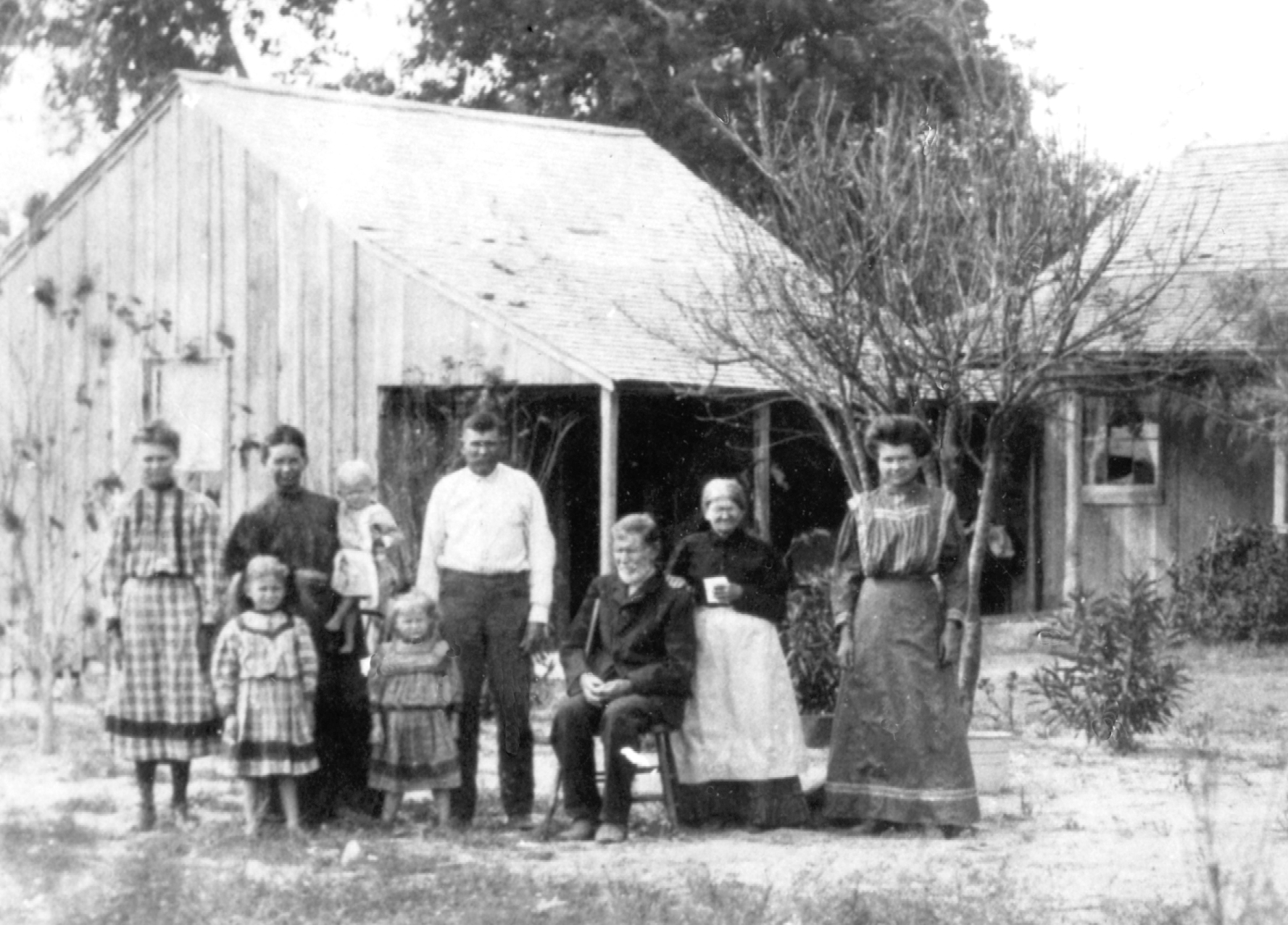

SAN ANTONIO • Panna Maria, the oldest permanent Polish settlement in the United States, is today a serene little community an hour’s drive southeast of San Antonio. At its center stands the gleaming white Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary Church, flanked by a large and sprawling oak tree and a gravestone capped by the bronze bust of a priest.

It is a far cry from the scene its Polish immigrant founders first gazed on Christmas Eve of 1854 as the priest who had brought them there, Father Leopold Moczygemba, OFM Conv, celebrated Midnight Mass beneath the sheltering oak.

There was no church, no buildings of any kind, just an endless expanse of dense, rattlesnake-infested brush that would need to be cleared before they could plant crops and build homes. As unhappy as their situation had been in Poland, it was not what they were expecting to find after uprooting their lives and spending perilous months at sea.

In Poland, whose war-racked history contained frequently changing borders and foreign domination, residents of Upper Silesia in what today is southwestern Poland struggled especially hard to survive with their culture and faith intact. Silesia at one time included parts of today’s Germany and Czech Republic but, by mid-19th century, what remained had come under Prussian control. Numerous wars and a revolution brought food shortages, further aggravated by potato blight and a flood of biblical proportions. Widespread famine and devastating outbreaks of cholera and typhoid fever occurred, and with the increasing poverty came a frightening rise in lawlessness.

“They were farmers over there,” says Bishop Emeritus John W. Yanta, a descendant of Panna Maria’s Silesian immigrants. “They had land, but they had very little land and they had to pay high taxes to the nobles.” They also had conscription, being required to serve in the Prussian Army or its reserves until the age of 60.

When one of their own, Father Leopold Moczygemba, a young missionary priest serving the German-speaking populations of Castroville and then, New Braunfels, wrote home to family in Silesia, it seemed the answer to their prayers, related Bishop Yanta. “The German-Americans are prospering here in Texas,” he told them, “and you can do the same thing. Please come to Texas.” His letters were passed around to relatives and neighbors and the first group of immigrant families packed up their necessities and sold the rest, leaving home in 1854 for what they hoped would be a better life in an unknown land. More groups followed throughout the 1850s.

Crossing the Atlantic took nine weeks in crowded, often unhealthy quarters on cargo ships, with those who died enroute being buried at sea. Two sets of Bishop Yantas’ great-grandparents, the Yantas and the Kasprziks, traveled on the same boat, which docked in New York in 1855. Three days later, the Yantas’ infant son, Nicolaus, died and was buried there. The Kasprziks were not as fortunate. Their three-year-old daughter, Johanna, had died at sea and her body was committed to the waves.

Bad drinking water on the ship the Notzon family sailed on resulted in sickness and deaths, including two of their children and, finally, the family patriarch himself, a robust man who had selflessly shared his cask of wine with the sick in place of the tainted water. His pregnant widow and four remaining children arrived in Indianola alone and she soon wed another Silesian immigrant, a widower with seven children.

After the first ship carrying Silesian immigrants, the Weser, landed at Indianola, the travelers hired oxcarts to take their belongings to San Antonio. Many walked alongside the carts the entire two-week journey.

Father Moczygemba had originally hoped to establish a Polish settlement near New Braunfels, but this did not come to pass. Instead, through John Twohig, a banker, he purchased land in Karnes County, which unfortunately turned out to be much more expensive. It was near the confluence of the San Antonio River and Cibolo Creek, but miles from civilization. (As one early resident wrote home, it did not matter if you brought money from Poland, for there was nowhere to spend it.)

Reaching San Antonio, the pioneer Silesians were then led by Father Moczygemba on a three-day trek to the wilderness site of the future Panna Maria (Virgin Mary), where Christmas Midnight Mass was celebrated under the large oak tree that stands by the present church. The weary travelers dug shelters out of the earth for their first homes, sod dwellings and lean-tos with thatched roofs. They erected a humble church and began the laborious task of clearing the land for farming.

Early on, some families headed to Bandera, where a town was already established and free transportation there provided by sawmill owners, if the immigrants agreed to work for them. It was on the edge of the frontier however, and subject to deadly Indian raids.

In Panna Maria, there was much unhappiness with the primitive conditions to which Father Moczygemba had brought them, with some threatening his life. He tried to help as much as he could and wrote to Europe requesting Polish priests, but none were sent, and with his pastoral duties elsewhere, in addition to being the head of his order, it was a difficult time for him. Before long, he was assigned to northern states into which new waves of Polish immigrants were moving, later founding the first Polish seminary in America.

With more arrivals, new Polish settlements formed in St. Hedwig (Martinez), Cestohowa, Pawelekville, Kosciusko and Cotulla. Polish immigrants contributed to the development of many other towns as well, including San Antonio, where the Polish community centered around St. Michael Church, later razed for HemisFair ’68. When a severe drought ravaged Texas, some headed for greener pastures in Missouri.

Although against slavery and conscription, many Silesian Poles were conscripted by the Confederacy during the Civil War. When captured, a number willingly switched to the Union Army. After the war, Polish communities suffered harassment by lawless Southerners. The Poles served proudly in World War I, but faced harassment by the Ku Klux Klan for their Catholic faith and Polish heritage on their return.

Through it all, their Silesian language and customs, were steadfastly maintained, culminating in the nearly completed 16,500-sq.ft. Polish Heritage Center at Panna Maria, whose mission is to preserve for posterity the values, beliefs and traditions of the first Silesian Polish settlers and their descendants and inspire and inform all visitors. Leading the project is Bishop Yanta, whose paternal grandmother, Albertina Kasprzik Yanta, was unexpectedly born beneath the church’s oak tree when the family came to town to attend Mass one long ago Sunday.

He led the first pilgrimage of Silesian immigrant descendants back to Poland in 1973, after studying there to learn more about his own heritage, having immersed himself in Hispanic and African-American heritages in his early ministries in San Antonio and as the bishop of Amarillo. These pilgrimages were then taken up by Father Franciszek “Frank” Kurzaj, a priest from Poland serving in the Archdiocese of San Antonio, who has published a book, Silesia for Silesian Texans, to further educate these sons and daughters of Polonia.

And while the Polish priest who started it all, Father Leopold Moczygemba, did not live to see the children of his Silesian settlers “rise up and call him blessed,” his remains were lovingly reinterred in 1974, from a Detroit cemetery to a grave beside the historic Panna Maria oak, where his bronze likeness welcomes all who come to the church.

Sources: The First Polish Americans: Silesian Settlements in Texas, T. Lindsay Baker; Silesian Profiles: Polish Immigration to Texas in the 1850s and Silesian Profiles II: Polish Immigration to Texas 1850s-1870s, Silesian Profiles Committee; Silesia for Silesian Texans, Msgr. Franciszek Kurzaj.

Spread the Good News

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Linkedin

Pinterest

Snapchat

Youtube

SUBSCRIBE. FOLLOW. LIKE.

Stay up to date on social media about current events, breaking news, national and international news. View photo galleries, videos and more. Use #iamTodaysCatholic to tag us!