The Missions: past, present, future

BY CAROL BAASS SOWA

TODAY’S CATHOLIC

This is the second in a multi-part series.

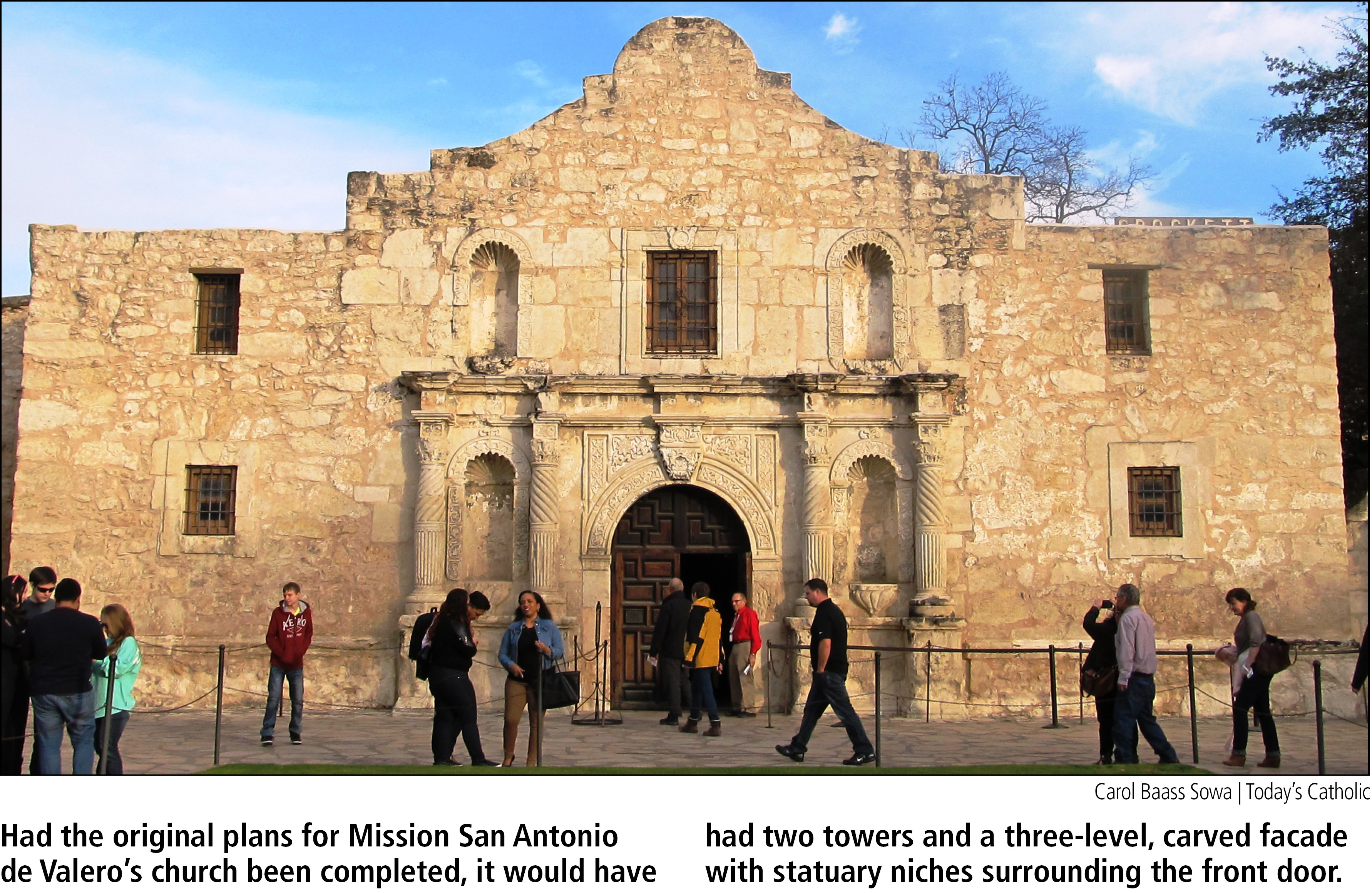

SAN ANTONIO • At the time of Mission San Antonio de Valero’s secularization in 1793, what was to have been its third and permanent church still stood unfinished. Master mason Antonio Tello had unceremoniously fled town with a murder charge over his head only a few years after commencing work on it in the early 1740s, leaving additional unfinished jobs at missions Concepción and San Francisco de la Espada. Valero’s church walls were left about four feet high.

The undaunted friars apparently attempted to continue the work without the requisite master mason, raising the walls possibly as high as 25 feet and working on a bell tower and flat roof — until the building collapsed. A string of master masons and artisans were hired over the decades that followed. By 1759, most of the facade’s carved stonework was in place. Around 1763, ceilings of the ground floor bell tower rooms and the sacristy were finished, the latter allowing church services to move into the sacristy. However, the church remained roofless.

Work came to a final halt in 1772, when Valero was transferred from the Querétaran Franciscans to those from Zacatecas, whose priority was their mission church underway at Mission San José. When Valero was secularized, the sacristy was still serving as the church, the façade was unchanged since 1772 and temporary wooden roofs were leaking badly.

At secularization, Valero’s mission lands were divided among its native inhabitants and they were allowed to remain living in the 12 still inhabitable compound buildings. In 1802, a Spanish light brigade, the Second Flying Company of San Carlos de Parras del Alamo, took up residence in the convento, living there intermittently until 1836. (They spent two years posted at the Brazos, charged with stopping the illegal immigration of Anglo-Americans into Texas.) At Mission Valero, they added buildings and, inadvertently, a new name — the Alamo.

The brigade’s presence prompted the setting up of San Antonio’s first hospital in the convento, necessitating major repairs. The majority of flat cement roofs were replaced, most walls patched, plastered and white-washed, many floors and a couple of walls rebuilt, and rotten beams and roof drains replaced.

When the Mexican Revolution kept the “Alamo brigade” away from San Antonio for nearly a decade, the mission buildings again deteriorated, with walls and roofs collapsing and citizens demanding the right to purchase mission properties. The government finally consented to this in the late 1820s.

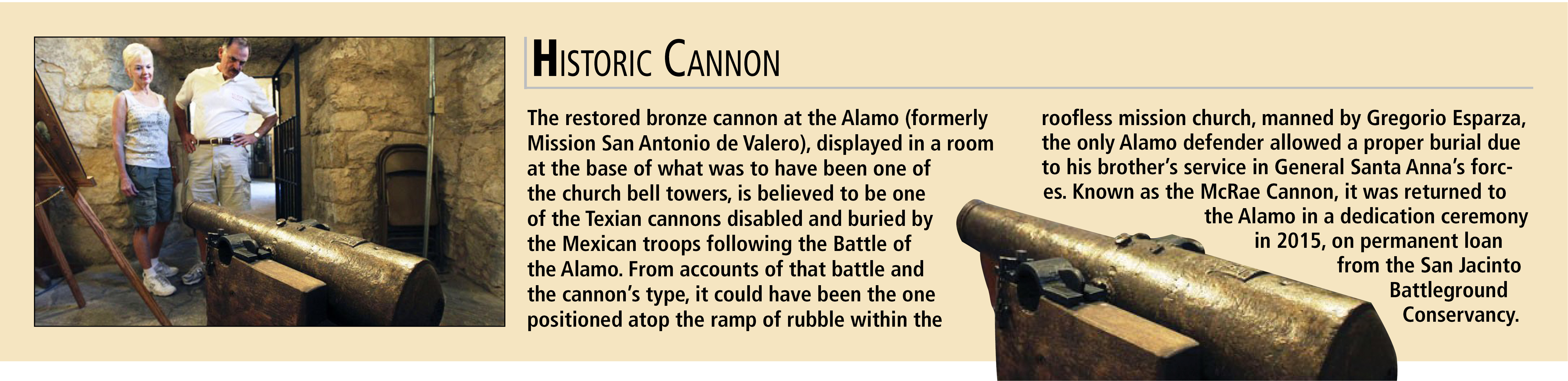

The onset of hostilities with Mexico brought new activity to the unfinished mission church, as General Martin Perfecto de Cos, commander of the Mexican forces in Texas, prepared to fortify San Antonio and the Alamo in 1835. Ribs of the unfinished church roof were pulled down and mixed with convento rubble to construct an incline for hauling cannons to the top of the roofless church. After San Antonio was reclaimed by the Texians, the ramp was likely the one used by the Alamo defenders in 1836.

Following the Texians’ victory at the Battle of San Jacinto a month later, the Mexican troops in San Antonio destroyed defenses at the Alamo, leaving it in ruins before departing. Repairs were not initiated until 1846, when the Alamo became a U.S. Army Quartermaster Depot, leased from the Catholic Church. Army repairs included the church’s first roof and addition of the now iconic curved parapet.

During the Civil War, the former mission served as a Confederate Army depot, reverting to the United States at the war’s end. In 1877, following its move to Fort Sam Houston, the army relinquished the Alamo property to the Diocese of San Antonio, which sold the Alamo chapel, as it was called, to the state of Texas in 1883.

The convento had been sold earlier to private owners for a store and warehouse, later becoming Hugo & Schmeltzer’s massive mercantile establishment, whose building incased the convento/Long Barracks. More changes and demolition to structures in the mission compound occurred as the town grew.

Through the efforts of Adina De Zavala, Clara Driscoll and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT), to which they belonged, the state purchased Hugo & Schmeltzer’s in 1905, turning over both it and the Alamo chapel to the custody of the DRT. Sadly, the two women came to a parting of the ways over the Long Barracks, with Driscoll believing it was not the original building of 1836 and should be torn down, while De Zavala held it to be not only genuine, but more significant in the Battle of the Alamo than the chapel. Their disagreement expanded into a court battle. While Driscoll went on to lead the DRT, De Zavala was later found to be correct in most of her historical contentions.

Over the years, adjacent land was acquired, a park and buildings added and the Alamo’s present concrete, barrel-vaulted roof installed. Preservation work was also carried out. In 2015, the state formally assumed control of the Alamo and it was placed under the Texas General Land Office, with new preservation and interpretation being planned.

The mission church that never saw the glory of completion, instead, achieved honor as an international shrine to liberty and, in 2015, a World Heritage Site.

Next: Mission Concepción

Primary sources for this article were “San Antonio Missions: Nomination for Inscription on the World Heritage List,” Paul T. Ringenbach, lead author; and “Of Various Magnificence,” James E. “Jake” Ivey, National Park Service, excerpts now available on [eltdf_highlight background_color=”” color=”Blue”]www.nps.gov/saan/learn/historyculture/ovm.htm.[/eltdf_highlight]